A talk given by Tam Ward at Quothquan near Thankerton, some years ago.

History can be mystery and archaeology can be downright frustrating, often, literally, archaeology is rubbish! It’s all about trying to understand and learn about the past, neither of the disciplines is easy.

One would think that history should be the easier of the two since it deals with the written past or even more up to date events within living memory. That’s because we are fed selective bits of the story, and it depends who is telling it, whether we get the truth, half-truth or downright lies. Historians are just typical humans, they embellish the tale a little here and a little there, the same as we all do when telling a story, and we tell it the way we want to, perhaps to make it more dramatic, funnier, or to serve some more sinister purpose.

It can be even more complicated when researchers delve into the records, who produced the record in the first place – and why? is the researcher being thorough enough or a bit slip shod? are all the records there in the first place? and so it goes on.

A key word in all of this is “research”, literally going through data again by ‘re searching’, for the second, or numerous subsequent times, it’s easy to see how interpretations can change.

Archaeology depends on two things; people digging objects from the ground and then interpreting what they are and how they got there. The duty on the archaeologists is to retrieve all the information in the ground accurately and then preserve that information, be it an object, a soil sample or the record of what was there, this is often done in the form of photography and perhaps drawing. If a good record is made, then future researchers have a chance at working out what it all means, if the record is poor, then no one will ever be able to make sense of it, it’s the same with historical record.

So, there is a heavy burden of responsibility on the excavating archaeologist because they are providing the source information, the only available information on a site, and it can never be re-done. Then the fallibility kicks in when the archaeologist interprets what has been found, but if he or she gets it all wrong, at least others will have an opportunity to re interpret the evidence if it has been retrieved and recorded.

History and archaeology are not sciences such as chemistry, physics etc, where hypothesis can be tested and re-tested and proved one way or another. Historians and archaeologists therefore have a huge duty of responsibility to get the truth out of the evidence, in whatever form it becomes available.

This offering concerns a few local history myths around the town of Biggar, presenting the available evidence garnered from local sources, and some from further afield.

The myths

- Tinto Hill was a volcano

- William Wallace walked over the Cadgers Brig

- William Wallace fought a battle known as The Battle of Biggar

- Lord Fleming and the murder of Comyn in Greyfriars church Dumfries

- The Biggar Bonfire dates to “time immemorial”

- The Riding of the Biggar marches was a traditional event in Biggar

- Secret tunnels

- The size of Biggar Cross and Cross Know

- Biggar Fountain was scrapped for the WWII effort

- Did Biggar have a bastlehouse?

1: Tinto Hill was a volcano

Tinto was never a volcano, but it was a mass of magma trying to be one. A volcano erupts on the surface of the planet, firing out a variety of substances which are the geological matter lying immediately below the surface. The minerology of most volcanoes is unique because of the circumstances of where it is on the planet and how it erupts onto the surface and into the atmosphere. Therefore, volcanos leave a fingerprint in their outputs, which, in true detective style, can be traced back to source.

In the past, it was easy for geologists to say where a certain volcanic lava flow came from, because it did not generally get far from its source. However, matter which is shot high into the atmosphere as tephra; tiny particles which become airborne and are carried around the planet on prevailing winds, have only in recent decades revealed their secrets. Geologists, aided by sophisticated science can say where such particles came from, and even more incredibly, say when they were emitted.

One of the main sources of this astounding claim is the Greenland ice sheets, which for thousands of years, have locked away in their layers, the annual deposition of any matter which fell on them, and this also includes evidence of the atmosphere of the planet in each year. Antarctica works correspondingly well for the southern hemisphere as scientists are nowdiscovering.

Anyway, of interest in this matter locally; during the recent research into Scotland’s oldest known people at Howburn Farm, a nearby ‘kettle hole’ was cored to a depth of 13m by Richard Tipping of Stirling University, aided by members of the Biggar Archaeology Group. The purpose was to discover any evidence of the hunters of the Late Upper Palaeolithic period whose 14,000-year-old camp site lay nearby, beside the A702 road. It was revealed that the deposits were later in time, however, and perhaps one of the easiest dates to remember about Scotland’s past was forthcoming because of the work. 12,121 years before 2010 when the coring was done, a volcano in Iceland erupted and deposited some of its dust in a loch at Howburn, one simply cannot get more accurate than that, and all backed up by peer reviewed scientific evidence. Incidentally, the work also showed that the south of Scotland had been more affected by the last mini ice age around 12,000 years ago, than was hitherto known. It was a fantastic update on the geological story of Scotland, just a few miles from Biggar and all stimulated by the work of the local voluntary archaeologists.

But to get back to Tinto, it is by detailed examination of the evidence by geologists over centuries of study, that determines the true nature of the hill. Examination of evidence being the underlying theme of this paper.

Tinto is composed almost entirely of a rock called felsite and the neighbouring hill to the north; Cairngryffe, is part of the same geological stratum. The rock was of course famous at one time for its use on Lanarkshire roads, being known everywhere else as ‘The red roads of Lanarkshire’, since most other roads in the country used black basalt chips on their surfaces. It is still prominent today as a decorative material on road sides and roundabouts and on countless garden paths anddriveways.

The structure of Tinto is known in geological jargon as a “hypabyssal intrusion, a large laccolith” (BGS 1979 & 1985) which means in common language; a mass of molten material bulging up from deep in the crust – but which never reached the surface,it solidified as a domed mass with a flatter base, if it had reached the surface – it would have been a volcano. Eventually all the softer rocks above and around it (which it had pushed through), were eroded away to leave the dome shape we now call Tinto. Tinto was never a volcano.

For a recent story of the history surrounding Tinto see On Tintock Tap – A report on Tinto Hill Lanarkshire, Ward 2016.

2&3: William Wallace walked over the CadgersBrig in Biggar at the time of the ‘Battle of Biggar’ 1297

The greatest of Scottish patriots William Wallace was horrendously put to death in London by his adversary Edward I in 1305. This and a few other well documented facts about the life of Wallace and his final demise are generally accepted history.

However, a considerable amount of the exploits of Wallace are quoted from a poem written by a chap known as ‘Blind Harry’ and who lived between the years c1440- 1492, writing his epic story of Wallace about 172 years after Wallace died. Harry was apparently a court minstrel and his main claim to fame was “The Actis and Deidis of the Illustere and Vailzeand Campiount Schir William Wallace, Knight of Ellerslie”, in which he tells, among many other things, of the Battle of Biggar, when Wallace defeated a superior English army after spying on their camp dressed as a beggar or cadger.

There is no historical foundation for such an event and it seems that this part of Harry’s tale is confused with the Battle of Roslin which did take place, although later in 1303. John Comyn and Simon Fraser mustered troops from the SW of Scotland at Biggar and marched from there to Roslin where they had a spectacular victory over a superior English force. It seems Wallace was absent from the event, possibly lacking confidence after his humiliating defeat at Falkirk by the ‘Hammer of the Scots’ in 1298.

Further confusion may have arisen from the fact that 1297 was of course the date of Wallace’s famous victory at Stirling Bridge.

The Battle of Biggar is supposed to have taken place to the NE of the town and the Redsyke Burn supposedly takes its name from the copious quantity of English blood which ran down its course after their slaughter. Support for the tale is that “old pieces of armour are found from time to time on the site” (Hunter 1847).

The Cadgers Brig which is incorporated into local myth as the bridge Wallace crossed to and from his camp on Tinto Hill to determine the English strength at Biggar, certainly did not exist at the beginning of the 14th century. Few credible architectural historians would place it earlier in construction to the 17th or 18th centuries, and probably the latter. It is a ‘pack horse’ bridge, used by local people and itinerant travellers (packmen or cadgers) who would sell their wares from the back of a horse. The old ford beside the footbridge would have been used for wheeled traffic (horse carts) on their way up the Wynd, which was the main road out of Biggar before Thomas Telford created new roads across the area in the early 1800’s. The route up the Wynd was the road to Lanark, leading by Langlees, Cormiston, Boat Bridge at Thankerton, Cloburn Farm and down to Hyndford Bridge, where before 1773 there was a nearby ford across theClyde.

Cadgers Brig.

Post script: Robert the Bruce, William Wallace, Mary Queen of Scots and Mary Fleming DID all walk over the Cadgers Brig, together! as photographic evidence shows. However …

The full details of Blind Harry’s account are considered by Hunter (ibid) in his acclaimed local historical account of Biggar, although reservations are given, he cites the discovery of silver pennies of Edward I from Biggar and Crosscryne, as possible evidence of the event. The discovery of these coins is true, they are now on display in Biggar Museum. However, what Hunter did not know at the time was that the various coin hoards with Edward I face on them, also included coins of his son Edward II and it is near certain that they were all lost in October 1310 when King Edward II was camped in Biggar on his sojourns in to Scotland to pretend to subdue the country as his more ruthless father had tried. In fact, the ten pennies from the Crosscryne hoard are all Edward II coins (Pl 2). However, another hoard of six coins found at Logan in Tweedsmuir were all Edward I pennies (Ward 2013).

Another fact about the period was that the English determined that part of the Anglo- Scottish border would run from Carlops to Cross Cryne at Biggar giving the English all the territory to the east of that line, i.e. the whole of the Borders. Recorded by Wynton in his “Cronykill”; “Karlinlippis and at Corsecryne – thare thai made the marches syne”, it is unlikely that the Scots paid much attention to it.

There was no Battle of Biggar presided over by William Wallace, nor could he have walked over the Cadgers Brig. Apart from local myth, no armour or armaments are recorded to have been found on Biggar Moss, the location of the supposed battle. The story of the Battle of Biggar and any association of the Cadgers Brig and William Wallace are – myth.

4: Lord Fleming and the murder of Comyn in Greyfriars Church

The story of Lord Robert Fleming’s involvement when Robert Bruce infamously slew John Comyn at the high alter in Greyfriars Church in Dumfries is well known.

When Bruce came out of the church and stated; “I doubt I have slain the Comyn”, — Kirkpatrick, followed by Fleming and others went into the church with Kirkpatrick alleged to say “doubt? I’ll mac siccar” [I’ll make sure]. Fleming is supposed to have held the bloody head of Comyn up and declared “let the deed shaw”. Later, Fleming got his reward from Bruce by the granting to Fleming of Comyn’s lands at Cumbernauld.

As a direct result, the Flemings adopted the motto; “Let the Deed Shaw” [Let the deed show] and it subsequently became the motto of Biggar Town Council in 1930 on its own coat of arms (Pl’s 5 & 6).

and motto.

The murder of Comyn took place only six months after the murder of William Wallace by Edward I in London. What should always be remembered is the fact that nine Flemings, including Robert (above) signed the Ragman Roll along with Robert Bruce in 1296, William Wallace never signed that cowardly document of homage, but paid a heavy price. Robert Fleming then went on to help Bruce after Greyfriars, both of them breaking their sworn bond to Edward I. Fleming’s ultimate reward from Bruce were the lands of Comyn in Cumbernauld.

Much of the above is recorded history and may be accepted as such. However, the business of Fleming’s involvement, apart from his presence at Comyn’s murder, is entirely unsupported by primary historical record, as far as is known. The act of severing Comyn’s head and holding it up to present it to Bruce by Fleming, is therefore a traditional account of what happened on that day. It could be described as folklore and possibly began as ‘oral history’ before finally appearing in print as ‘history’.

This writer, in this case, is cautious in describing the event as ‘myth’, since the Fleming motto ‘Let the Deed Shaw’ must have originated somehow, and the story may be true. What is important to remember is that it is unsupported bydirect evidence, as indeed, much of so called ‘history’ is.

5: Biggar Bonfire

The spectacular annual event, unique to Biggar on his grandiose scale, of ‘burning the old year out – and burning in the new’, with a massive street bonfire on Hogmanay, is reputed to date from “time immemorial and the times of the Druids”.

When one researches for references to this event, surprisingly, the evidence points to the tradition as being relatively modern.

Biggar, and Lanarkshire, have two scholarly local history publications dating to the mid-19th century; they are Biggar and the House of Fleming by William Hunter in 1887 (Hunter 1887), and The Upperward of Lanarkshire Described and Delineated by Irving and Murray in 1864, in three volumes (Irving & Murray 1864). The detail given in each set of books is extraordinary and between them they cover local traditions, history and the state of archaeology, natural history and geology as was known at the time. The district is fortunate indeed to have such valuable reference books which give citations for their sources – but only in Hunter is there any mention of Biggar bonfire! It is to Hunter that we have the reference to “time immemorial” “and most likely had its origins in remote superstitious times”, however he does comment it was an active event in 1836.

Although the bonfire appears to have been burned on the ‘Cross Knowe’ it must have been quite large at that time as it is reputed to have cracked the cross shaft necessitating its removal. Hunter also makes an interesting comment that attempts were made to stop the custom “on the ground that it is injurious if not dangerous to the neighbouring buildings”. Similar futile attempts were made in the last quarter of the 20th century, but appropriately resisted.

In 1900, Crocket writes that “Biggar Cross was removed in 1823 when the knowe was levelled for street improvement. The cross had a date of 1632. At its apex which was square it had vertical dials on each side and the initials J.E.W. and the date 1694 [John Earl of Wigton]. Possibly a renovation. No sport could rival the ‘hurley-hacket’ at the Cross Knowe; and the bonfires that blazed forth on the last night of each year, “burnin, the auld year oot”. It (the bonfire) is still to the fore by the Fountain side [now itself removed]. It was on one of these occasions when news arrived (1820) that the Government had abandoned the Bill of Divorce against Queen Caroline – that the cross was destroyed, split and shattered by the intense heat, and had ultimately to be taken down”.

Here then is a reference to the bonfire existing long before both the publications cited above were produced, but Crocket is writing some forty years after them!

According to Hunter, fires were lit beside the cross to celebrate various victories of the Napoleonic Wars, and it was on a similar occasion (Crocket above) that the cross was broken.

O wae (woe) is me for the auld Cross-knowe;

Twice forty years hae come and gane (have come and gone)

Sin’ first I sprauchilt (scrambled) up its browe,

A wee bit thochtless, happywean. (small thoughtless happychild )

Noo a’ day long I sit and grane (groan),

And scart wi’ grief my lyart powe (scratch my beard),

To think there’s neither yird nor stane (scratch my beard)

O what was ance (once) the auld Corse-knowe.

The poem in Scots vernacular about the removal of the Cross Knowe was composed in c1852 by Robert Rae, native of Biggar (1805-1861). It is given by Hunter and is entitled “A Yammerin’ Auld Man’s Lament for Biggar Auld Corse-Knowe”, in it the poet laments all the activities no longer enacted on the Cross Knowe, including the bonfire. The first, of thirteen verses of which is here given:

A poem by Alexander Steele, buried in Biggar, is given in “View of Biggar from the summit of Hartree Hills” – “The games, the fairs, the New Year fires on Biggar’s auld Cross-Knowe”.

During the WW II years and because of the ‘blackout’ being imposed, the lighting of such a bonfire was prohibited. However, some local worthies, notably Bobby Moore, ensured the tradition of ‘Burning the Old Year Out’ in Biggar was maintained, when a few cardboard boxes were quickly lit and then immediately extinguished ‘after the bells’.

A comparable situation came about in 2006 when Barbara Scott was to have the honour of lighting the bonfire. Now, in an attempt to dispel any future ‘myths’ about this event, the following is given: A horrendous gale blew up the street, much worse than anyone had witnessed before on ‘Auld Years Night’. A decision had to be taken about the bonfire and under pressure (or orders) from the police it had to be cancelled. Only Hitler had achieved this before! To maintain the tradition, the policewere encouraged to allow a small fire for the ‘bells’ and allow Barbara to light it. This was organised not by the Cornets who usually take responsibility for the bonfire, but by the writer, his two sons; Stewart and Steven and by the McAlpine brothers Robin and Euan. Under the strictest orders not to allow the main pile to become alight, it was agreed to build a box with some pallets and cardboard boxes within, and see tradition maintained. The writer quickly brought the cardboard from the museum and the ‘Wee Bonfire’ was lit by Barbara just before midnight. It was a hearty blaze and many people stayed on to witnessit.

The Cornets then decided to have Barbara ‘light a candle in a box’ to maintain tradition. This was duly done – but after midnight and after the ‘Wee Bonfire’ was well and truly ablaze and the crowd had sung “A Guid New Year”. If anyone has any doubt regarding this event, it is all recorded on video by the writer, in the sequence given above. New Year’s Day saw lashing rain, as seen in the video, however, on that evening on the 1st January 2007, Barbara did light the main bonfire, thus becoming the only person to have burned in the New Year in Biggar – twice.

Strangely, in local newspaper reports on the event, only the ‘candle in the box’ was mentioned – another myth in the making?

The tradition of the bonfire can therefore be traced in historical record back to the beginning of the 19th century, about two hundred years ago, how much further back in time the event can be attributed to, must remain speculative.

6. Riding the Marches

In many Scottish towns, (not just the Border towns) Riding the Marches has a long tradition going back to times when boundaries between properties of landowners and administrative bodies were merely delineated with boulders. These rocks could of course be moved around to gain some extra territory by unscrupulous people. To determine that no cheating had taken place, the boundaries were inspected annually by interested parties, usually on horseback as the perambulations were often several miles long, hence ‘the Riding of the Marches’ (boundaries). Later in time, important boundaries such as property holdings were delineated by turf (or feal) dykes, then by drystane dykes, and latterly with post and wires fences, all accurately delineated on surveyed plans and maps.

Boundaries were important for economic reasons, especially in the 18th century when mineral wealth on an estate could be worth a fortune to the owners, a few metres of land could be vastly important. A local case in point were the boundaries between Lanarkshire and Dumfriesshire; the properties of the Hopetoun and Buccleuch Estates, where lead was extracted from mines and most importantly, the gold bearing rivers exist at Leadhills and Wanlockhead promised even morewealth.

As boundaries became more firmly established on the landscape, rideouts and inspections were unnecessary, however, since the events had transmuted themselves into traditional fairs and carnival events, Riding the Marches was retained as part of these activities, often being the raison d’être for them. Towns in the south of Scotland, most especially the Borders towns, now have these events as major aspects in their calendar of festivities.

Special historical events are sometimes re-enacted to maintain traditions, celebrations or commemorative dates; for example, the Battle of Flodden which Galashiels and Hawick take very seriously because of their proximity and connections with the battle field.

So, what about Biggar’s riding of the marches? Once again, if such events did take place in Biggar, there is no historical record of them. Some towns such as Biggar and West Linton had other equestrian festivals, usually formed as mutual benefit societies, Biggar had its Whipmen Society and West Linton celebrates its Whipmen Play each year. Membership of a Whipmen Society, as the name implies was open to anyone involved with horses; such as carriers or carters, and of course farming people.

Biggar Museum preserve the Biggar Whipmen Society records and their ceremonial banner, a rare piece of work painted on silk showing the horsemen in procession over the Cadgers Brig in Biggar (Pl’s 9 & 10). The banner was painted in 1807 by James Howe of Skirling; ‘The Man Who Loved to Draw Horses’ (Cameron 1986 & Malden 2015). One character is happily, or perhaps drunkenly playing the fiddle as he rides over Biggar Burn. The Society began in 1806.

Biggar celebrated its 525 anniversary as a Burgh of Barony in 1951, a re-enactment of ‘riding the marches’ was undertaken, with Brian Lambie acting as Cornet. In 1977 the event was re-established and has since became part of Biggar’s annual Gala Week festivities. A new Cornet is elected each year and the Biggar Riding of the Marches is now established – as a new tradition, perambulating the old Burgh boundaries much the same as is done elsewhere. The Biggar Cornet’s Club, much to their credit, have assumed most responsibility for organising the Gala Week and the Hogmanay Bonfire each year in Biggar.

There was no previous historical Riding of the Marches in Biggar before the above events, as far as may be determined.

7: Secret tunnels

There are secret tunnels leading between Boghall Castle and St Mary’s Church [The Kirk]. There may even be a tunnel leading from Bizzyberry Hill down to Biggar.

The idea of secret escape passages in castles and churches is a common one but is seldom founded on actual tunnels being seen. For an undertaking of building a tunnel between the church and castle in Biggar; a direct distance of 0.9km and one from Bizzyberry to Biggar church at c 1.6km, – is preposterous to say the least.

The geology of the ground upon which Biggar town lies is exclusively sand and gravel, laid down at the end of the last glaciation of Scotland and which is exploited as a significant resource at various sand and gravel quarries around the district. To drive an underground tunnel through such strata for any distance would be an undertaking of the most extraordinary kind and would require to be supported by stone or timber, in either case, an enormous resource of materials would be required, and the latter would soon rot away. Furthermore, any tunnel near the castle would almost certainly flood due to the drainage circumstances in that low-lying ground.

Boghall Castle got its name by the fact that it was originally surrounded by morass, being at the lowest level of the area, Biggar golf course is often flooded because of its low-lying position, being level with the castle. Imagine a tunnel running through this ground!

The church also lies on sand and gravel as anyone attending a funeral in the cemetery will have noticed. True, when the ground reaches Bizzyberry, it is solid rock. In a small rock quarry on the face of the hill there is a cave which could hardly be taken as a manmade tunnel. It is the product of human activity; a rock quarry, but not a deliberate tunnel. It is formed as only a few metres deep and less than 1m high along joints in the rock which were exposed in the quarry face when extracting building stone. An adult can barely lie within it. It was often spuriously cited as being another ‘Wallace hiding place or cave’.

Such features take on romantic interpretations to suit local mythology, just to make a delightful story – but unfortunately- not a true one.

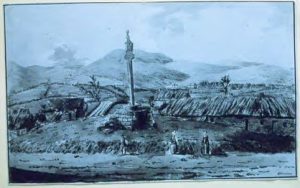

8. Biggar Cross and the CrossKnowe. Evidence from old illustrations

An example of how pictorial evidence of the past can be thoroughly misleading, is the engraving of ‘Biggar Cross – from a sketch by John Pairman in 1807’ (Pl 11). One thing about this illustration which can be taken for granted, is the fact that the cross was nowhere near the size given, when compared with the human figures surrounding it. The cross shaft is shown as four times the height of the people depicted standing beside it and, almost twice as thick as the bodies of the men. Parts of the cross may still be seen nearby, embedded into the south gable of the Corn Exchange, the realsizes can easily be appreciated Pl 15).

Another old illustration of the cross and knowe (Pl 12) show disparity with Pairmans sketch, both in shape and size. Note for example the tops of the two images of the cross, although the pictures appear to concur regarding the relatively large size of the knowe.

The crosses at Newbigging and Carnwath villages are still standing and give a good indication of the size that Biggar Cross would have been.

Not only the written or printed word can be suspect regarding truth, images can also deceive, this is especially true of sketches or paintings where ‘artists licence’ may prevail. However, from its outset, photography has easily been made to lie and this is even more simple with modern techniques available to anyone with a digital camera and a computer. The lesson is not just “beware what you hear or read” but “beware the truth of images”.

9: Biggar Fountain was removed for scrap metal for the War effort

The Jubilee Fountain (Pl’s 16-19) was installed on Biggar High Street in 1887 to celebrate Queen Victoria’s 50th anniversary on the throne. From old postcards it can be seen to be a major and attractive piece of street furniture, one which any small town should have been proud of. The cast iron components of the fountain are often stated as having been removed for scrap metal for the war effort, numerous garden railings were taken for this purpose and the stumps of the railings are evident on many garden walls today.

used as a garden in post War years, before finally being scrapped.

However, the demise of the fountain took place in 1947, giving the lie to the war effort story. The sad truth is that the then Biggar Town Council members wanted rid of the fountain which was then seen (by them?) as an eyesore, not working and not cared for. It was laterally filled with soil and planted with flowers, even more work to maintain. So, in typical self-fulfilling prophesy, it became perceived as a blot on the street scene, and without much protestation was removed. Fortunately, the late James Cuthbertson of local engineering fame, and who also engaged in much re-cycling of ex-army vehicles for scrap and renovation into weird and wonderful innovative ideas, managed to save four of the spouts; cherubs sitting on dolphins and with littlespears.

They are now in the possession of The Biggar Albion Foundation Ltd, and with only a small amount of imagination and effort, Biggar could once again have a bit of its elegant past restored.

10: Did Biggar have a bastlehouse?

= a bastle house?

Bastle houses were the last defensible houses to be built in Britain, constructed at the end of the 16th century and in direct response to the infamous Border Rievers. The were a cut down version of a laird’s tower house (Pl 21) being living accommodation above an often barrel vaulted basement used as a byre and for storage. Clydesdale has an unusual concentration of such houses so far removed from the Anglo-Scottish border where most are to be found in both England and Scotland, the Clydesdale sites are the only excavated examples in the country. Often associated as country dwellings, however, Border towns are known to have several examples built on their streets, Peebles for example is supposed to have had about six, they were used as refuges during time of attack and would have been effective in protecting the occupants as long as any attack was shortlived.

Two types have been recorded in Clydesdale; a long type and a short type, all the Clydesdale examples had vaulted basements. Biggar Museum has a scale model (Pl 23) of one, known as Windgate House and which was excavated near Coulter and, a display of the story and the excavated artefacts from the Clydesdale bastle houses.

It is known that Biggar town was attacked by Rievers around 1600, and therefore the need for a strong defensive building or buildings to protect the town inhabitants is an appealing hypothesis. However, is it true? A place name; Langvout (Pl 20), which commemorates a building now long gone, but which stood nearly adjacent to the Museum, is the clue – the Long Vault. It is unlikely that even archaeological investigation of the site could now prove much, but the place name seems to suggest such a site. One difference between bastle houses and the loftier tower houses was that many bastles were long in ground floor plan, while the towers were shorter, meaning that the description ‘Langvout’ is unlikely to refer to a tower house.

Did Biggar have a bastle house? The truth is we don’t know for sure, but it may have been likely.

Conclusion

Traditions must begin at some point, sometimes they wain and are resurrected, sometimes they simply cease to exist, while new traditions develop. Traditions are extremely important to all cultures, whether national or local, the very fabric of civilisation depends on traditions being maintained, it could be called cultural heritage and as such it is often what a culture bases itself upon, spiritually, politically or ethnically.

Myth however, is often a hindrance to understanding the past and the true lessons it can teach us, although, sadly, the human species seems incapable of learning much from the past and continues to make the same ridiculous mistakes, with the predictable result, human misery – for some, and wildlife misery – forall.

Myth is great, for uninformed entertainment, for a delightful story, or perhaps a film, and why should the truth ever get in the way of a good tale? Some so-called myths may of course have a grain of truth in them, and become the basis of future discoveries and theories, but for the most part it seems that it is the basis of ‘fake news’, to coin a modern term.

Myth, as the dictionary defines it is – “a commonly held belief – that is untrue”; a story without foundation.

Well what has all this got to do with Biggar? which, like most places has its own share of myth and fanciful history if what is presented above can be accepted. If we take the time and effort to look beyond the myth for a delightful story, we find it, quite easily; Biggar and the surrounding district has a colourful past which is presented in historical and archaeological record, and while neither of the two can be definitively 100% truth, they are the nearest to acceptable truth as one can get.

We have the stories of the Flemish and/or Norman invaders into Clydesdale under the patronage of David I and his grandson Malcolm IV, the names of these invited foreigners resonate through our historical archives, for example Baldwin De Bigre, the first Sherriff of Lanarkshire, his numerous contemporaries who have uniquely left their names to the settlements which are now our surrounding villages such as Lamington and Roberton, the towns of Lambin and Robert who were actually brothers. Many other villages end their names with ‘ton’; the town of–.

While we have no record of Edward I ever being in Biggar, we certainly know of his son Edward II being here on at least two occasions, when some of his men lost their purses with silver pennies in several places.

The story of the Stewart dynasty in the 16th and17th centuries is inextricably linked to the Fleming family, and Biggar Gala Day crowning of the Fleming Queen DID happen at Holyrood, remarkable stories worthy of an epic film, and all recorded history. Biggar Museum displays the oldest known gun to exist in Scotland; the Boghall Gun was possibly made in France and dates to the early 15th century, it is older than the more famous Mons Meg seen in Edinburgh Castle, as authenticated by leading specialists.

Numerous characters and events continue to modern times to colour the story of Biggar and district, there is no need for myths when we have such good history.

Biggar Kirk is unique in Scotland; being the last Pre-Reformation church to be built (1545-1547), complete with its own well documented murder story and conflict between the Biggar Flemings and the Tweedies. The church is also highly unusual as being a defensive church with battlements and gun ports, reflecting the turbulent times when it was founded (Ward forthcoming 2019).

Biggar has the only surviving small town gasworks left in Scotland, open to the public as an industrial museum. It was built in 1839 and the retorts for cooking the coal to extract the gas – are original.

Several other famous and well-known and also perhaps less well-known but important names are associated with Biggar from the 19th century;

George Meikle Kemp, was a self-taught architect who designed the iconic Scott Monument in Princes Street, Edinburgh, he was born at Hillrigs Farm in 1795.

Adam Sim of Coulter Maynes was an antiquarian of national repute, much of his amazing collection of Scottish relics is still on display in the Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh.

Gavin Cree was a nursery man where the present Moat Park Church stands, he invented and published (1828) methods of tree pruning and won a gold medal for his efforts, it was presented to him by Prince Albert.

Thomas Blackwood Murray, a son of Heavyside Farm, who in 1899 co- founded the hugely successful Albion Motor Company, having built the first few cars at the farm in Biggar, one of which is owned by Biggar Museum.

In 1940, during WW II, the Polish Brigade was stationed in Biggar for a while and the great General Sikorski reviewed the troops on the Main Street.

James Cuthbertson was a post war engineer who invented revolutionary snow ploughs and other heavy machines which were used worldwide.

Christopher Greave, better known as Hugh MacDiarmid, the acclaimed Scottish poet spent the latter part of his life at Brownsbank Cottage near Biggar.

These and many others all have stories told about them elsewhere, but all add to the true and non-mythical story of Biggar.

It does not stop there, we have pre-history on a par with few localities in Scotland, for example the oldest known site in Scotland and unique in Britain, at Howburn Farm where hunters of the Ice Age came on several occasions, all the way from Denmark walking over the area of the North Sea! That was 14,000 years ago, the book is now available at Biggar Museum (Ballin et al 2018). All discovered by our own local archaeologists, we can now tell of later hunter gatherers between 10,000 and 6000 years ago, there are more sites of these people in Clydesdale than in any other part of Scotland. We have the largest collections of Stone Age pottery ever found in Scotland, at Biggar Common and Carwood Farm, and other places, these date to between 5000 and 5900 years ago on scientific radio carbon dating. Nowhere in Scotland is there such a full representation of the Bronze Age as we have in Clydesdale and neighbouring Tweeddale, with house sites, burials, burnt mounds, ritual and ceremonial sites such as the amazing Blackshouse Burn henge near Thankerton, and the astonishing Wildshaw Burn Stone Circle near Crawfordjohn, much of these early stories are given on this website.

The Iron Age is represented by a most wonderful array of numerous spectacular hillforts and the Romans left their rich legacy along the Clyde in forts and roads. Two of the best examples of so called ‘Pictish’ silver chains were found in Clydesdale; one at Walston and easily the best example in the country, at Crawfordjohn, both displayed in the Museum of Scotland. Another object; also found at Walston is unique in Britain, a bronze ball cast with two entirely different types of Bronze.

Uniquely in British archaeology we have the excavated story of the Border Reiver times when tenant farmers lived in the last defended houses in Britain; bastle houses, of which there are now several heritage trails in upper Clydesdale. The Clydesdale Bastle Project provides the only archaeological evidence of the little known Lowland Clearances. Biggar has easily the best small-town museum in Scotland where all this wonderful – and true story, unfolds in a unique style of display using realistic models and actual objects.

Many unique objects of bronze, silver and gold are displayed in the National Museum of Scotland, they all came from around Biggar and Upper Clydesdale.

Of course, some of this story will change as research and further discoveries are made, but the difference between it and myth, is simply that it is founded on factual and scientific information, and not on some fairytale.

It is the easiest thing to create unfathomable mystery, simply make up a story – present it without any evidence, repeat it often, and then challenge others to disprove it. Without evidence they cannot. The credence of such stories are however apparently supported by including factual but non-associated truths; e.g. a named person who is known to have existed, or an existing or familiar building.

The distortion of history is easily understood by reading the work of writers such as Shakespeare in England and Walter Scott in Scotland. Their works are readily accepted by the non-enquiring or questioning minds as factual. Even in the cinema world where the filmmaker readily acknowledges their product may be fictional but based on a few facts, people insist on complaining that the film is historically incorrect, this was ably demonstrated after the film Braveheart was released, with two camps of thought often being expressed (and to this day still are); one lot accepting it all as fact, and the other complaining it is not! With a few people accepting it was merely an entertaining film, which, of course is all that it was meant to be, with no claim to being a documentary or a factual account of the subject matter. Thus it is easy to see how history is presented by both lay person and so called experts as a mish mash of verifiable fact, interpretation or opinion. The term re-search is often misapplied to mean – a new opinion, however well-established it maybe.

Traditions may be presented as beliefs and vice versa. Interpretation is perhaps the greatest enemy of truth, second only to propaganda or downright lies about an event or character from the past. It therefore becomes extremely difficult for the lay person to establish what may be the truth and what isnot.

History has much scope for ambiguity. Nearly all of history can be shrunk to a few original or contemporary sources, thereafter, the countless re-telling either orally or by the written word will add or subtract to a story, resulting in ‘interpretation’ being applied, and which is often way off the mark as far as factual or accurate presentation is concerned.

I leave some of the last words to the great French philosopher; Voltaire, who wrote “history is a myth upon which men have agreed”, and someone else wrote “Tell a lie often enough – and it becomes the truth”!

We do not need myth in Biggar for anything other than entertainment, for knowledge of our past we have nearly the lot, and as a wise person once said, “what we don’t have, is not worth having”, while a foolish person once said, “Don’t let anything as mundane as the truth get in the way of a delightful story”.