By Ian Paterson

I joined the Biggar Archaeological Group (BAG) only in 2003 when the Group was already long-established and, judging from the awards it has received from the BAA for its work, one of most successful amateur groups in the UK.

The origins of the Group date to 1981, when its current leader Tam Ward and two friends began to excavate the ruins of Windgate House [Figs 1a, b].

This building proved to be a bastle house – a farmhouse strengthened to resist attack by cattle reivers. Previously it had been thought that such buildings occurred only in the area closely adjoining, on both sides, the Scottish Border.

The discovery stimulated a search for further examples and the Clydesdale Bastle Project was born. A further dozen or so bastle houses, some still inhabited, were identified, and, where appropriate, excavated and consolidated.

In the case of the Glenochar Bastle [Fig. 2], in a campaign that lasted 9 years, a number of associated buildings were also excavated and the whole made accessible to the public by means of a Heritage Trail and an information board [Fig. 3].

In 1996, the Bastle Project received the Pitt Rivers Award from the British Archaeological Awards and The Heritage in Britain Award that is sponsored by English Heritage, Cadw and Historic Scotland.

A booklet published by Tam Ward in 1998 [Fig. 4] describes the Glenochar site in detail and provides summary accounts of a further 12 bastle houses in the Clydesdale area.

The Project is on-going. Wintercleuch bastle was not finally consolidated until 2003 and excavation and consolidation of Smithwood Bastle [Fig. 5], in the valley of the Daer Water, continued until 2007. Neither of these sites has been published as yet but an account of the numerous wine bottles recovered at the latter, together with those from Glenochar, is available on the BAG website.

In 1988, with the opening of the Moat Park Heritage Centre at Biggar, the Group took up its present role, although on an informal basis, as the archaeological arm of the Biggar Museum Trust. On behalf of the Trust, the Group has prepared exhibits and educational resources and, in 1990, established The Biggar Young Archaeologists Club [Fig. 6].

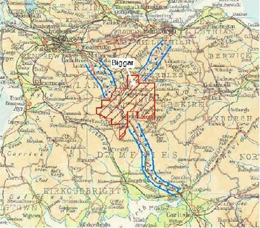

However, the primary thrust of the Group’s activities was and is the investigation, by means of field survey, including an annual fieldwalking exercise [Fig. 7], and excavation, of the archaeology in an area of almost a 1000 km2 that includes Biggar and parts of the catchments of the rivers Clyde and Tweed [Fig. 8]. Thus, the search for bastle houses was transformed into a series of major landscape surveys and field walking exercises

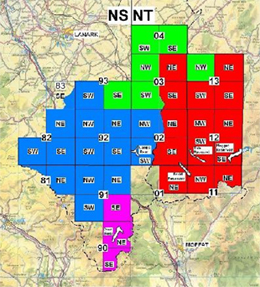

The first of these surveys, in the catchment of the Clyde and its tributary, the Daer Water, covered an area of more than 400 sq. km [coloured blue on Fig. 9].

Numerous hitherto unrecognised sites were surveyed and listed in Discovery and Excavation in Scotland for 1991 and 1992 and a detailed report deposited with the RCAHMS. This was followed by a survey, still on-going, of the area around and to the north of Biggar (green). In addition, surveys were carried out in the Manor Valley, in conjunction with the newly established Peebleshire Archaeological Society, and in Upper Tweeddale and in the area around the Megget Reservoir (red). The results of the last two of these were published on the Group’s website in 2004.

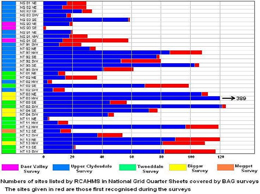

The impact of the surveys is evident from an examination of the records of the RCAHMS and Historic Scotland. A search of Canmore yields 2399 RC-listed sites in the BAG’s area of interest. Of these, 492, or more than 20%, were first recorded by the BAG [Fig. 10]. If ‘historic’ buildings and structures, such as most of the buildings fronting on to Biggar’s main street, are excluded from the RC list, the proportion would be even greater.

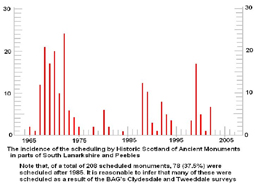

In the same area, Historic Scotland lists 208 Scheduled Ancient Monuments. Fig. 11 shows the dates when these were scheduled. The main peak on the graph without doubt reflects the initial scheduling by Historic Scotland of monuments recorded on the maps of the Ordnance Survey. Unlike the RCAHMS, Historic Scotland give no details of the source of their information. However, 78 of the monuments in the BAG’s area were scheduled by Historic Scotland after 1985. It is reasonable to infer that the scheduling of perhaps most of these, and certainly of 6 bastle houses, is the direct consequence of the surveys and excavations carried out by the Group. Perhaps most importantly, the surveys have located some 21 Mesolithic and Neolithic sites.

In 2006, the Biggar Archaeological Group was named as runner up for The Pitt-Rivers Award for its Daer Valley Project. This was followed in 2008 by the Pitt Rivers award for its Upper Tweeddale Survey.

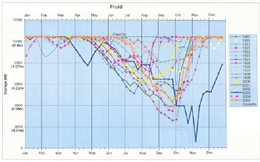

A significant number of the sites discovered by the Group lie within or alongside the 5 reservoirs – Camps, Daer, Fruid, Megget and Tala – that lie within the survey area. In all of these, as typified by Fruid [Fig. 12], the water level regularly falls over the course of the Summer by some 4 to 6m.

This exposes a tract of ground that has been stripped of most of its topsoil [Fig. 13], thereby revealing numerous archaeological features. On-going erosion of these, as the water levels rise and fall, is ample justification for their excavation.

In Camps Reservoir, survey and excavation revealed an archaeological landscape that included 2 Bronze Age funerary sites.

In Fruid Reservoir, the Group excavated two Bronze Age roundhouses [Fig. 14] that were being eroded by wave action.

One of these gave me my find of a lifetime [Fig. 15].

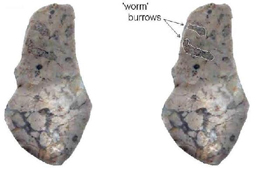

As reported in the BAG’s website, a number of Neolithic structures were excavated in Megget. Daer produced a number of Mesolithic knapping sites, dated at about 8500 B.P. One of these yielded an exotic ‘blue chert’ – actually a silicified limestone [Fig. 16] – that is not known to occur anywhere in mainland Britain except for one tiny flake from Airhouses.

Excavations at other sites in the Daer Valley produced typical microlith-dominated Mesolithic assemblages [Fig. 17].

An even more exciting lithic assemblage was found by standard field walking carried out over several years on the lands of Howburn Farm, beside the A702. An excavation [Fig. 18], carried out through the winter of 2005-6 yielded more than 1000 lithic fragments – 583 of chert, 444 of flint.

Diagnostic features of some of the flints [Fig. 19] convinced lithics experts Alan Saville of the NMS and Torben Ballin that, on typological grounds, the assemblage was of late Upper Palaeolithc date. A preliminary account of the material has been published in Lithics. (Saville, A., Ballin, T.B. and Ward, T. 2007).

A number of pits were found during the excavation [Fig. 20] but a C14 analysis of charcoal recovered from one of them gave a date of 200AD. Further excavations on the site, in the Summer of 2009, produced numerous other typical Palaeolithic flint artefacts, as reported on the BAG website.

So far, none of the excavations carried out by the BAG has attracted an award. Excavations are great fun but tend not to earn awards. Instead, it is the identification of hitherto unrecorded archaeological features through landscape survey and fieldwalking and projects that make archaeology accessible to the wider public by way of Heritage Trails, information boards and websites that win prizes.

Having said that, in the 5 years I’ve been a member, the Group has excavated, wholly or in part, 43 buildings and other features, including one Palaeolithic site, 7 Mesolithic sites – one being a 6000 year-old chert quarry – and 6 Neolithic sites. Almost all were under threat from erosion or from agricultural or forestry operations. Prehistoric sites are especially vunerable as they tend to consist of shallow pits and lithic scatters. I have taken part as a volunteer in professional supervised digs such as the Mediaeval cemetery at Auldhame, the Iron Age houses on Traprain Law and the re-excavation of the Roman Fort at Cramond. I can attest that the BAG digs fully meet the most exacting standards.

Not all the sites excavated by the Group are prehistoric. More modern structures, that were gradually disappearing as a result of stone-robbing, include, in addition to bastles, workers’ cottages and farmsteads dating from the 16th to the early 19th C. Such sites tend to produce significant quantities of finds – mostly pottery and glass shards – [Figs 21, 22,] – the processing and cataloguing of which can be time-consuming.

The success of the Group can be attributed in large measure to the dedication, not to say, fanaticism of its leader, Tam Ward, who has spent uncounted hours organising, supervising and recording field surveys and excavations, in the post-excavation processing of finds and soil samples and in the preparation of Reports.

However, the Group has benefitted greatly by the availability of work and storage space and other facilities, as well as financial support, provided by the Biggar Museums Trust. It is indeed hard to see how an amateur archaeological group can survive without such assets. Archaeological investigations are not cheap, even when staffed by volunteers. Over the years, the BAG has commissioned almost sixty C14 dates at a cost of some £20 000 at today’s prices. And from time to time, there are also fees to specialists. Over the years, the Group has benefitted from the support of numerous private and public sponsors including LADAS, PAS and Historic Scotland.

The results of the work must be made available. There is no more serious crime in archaeology than the failure to publish. Fortunately, digital reports are becoming increasingly acceptable but this means that a website has become a necessity. Through its website [Fig. 24], which in 2006 was commended by the judges of ‘The Mick Aston Presentation Award’, and has been further updated and improved since then, BAG is currently catching up on the publication of its projects.

Conclusions

There are lessons to be learned from the BAG.

- Strong, even dictatorial, leadership is essential. In the case of the BAG, this has been provided by Tam Ward – a driven man – prepared to devote uncounted hours to the Group’s activities. It is moot whether the Group will survive when he decides to hang up his trowel.

- Landscape surveys with fieldwalking are relatively cheap and win awards. Reservoirs are especially fruitful sources of new sites.

- As any structures discovered in reservoirs lie in the zone of active erosion, rescue digs are easily justifiable. Excavation is also justified in the case of sites, such as lithic scatters, that are under threat from aggressive modern farming methods or forestry.

- Be sure you can finish what you start. The Glenochar Bastle Project ran for a gruelling 9 years. The Fruid Bronze Age roundhouses took 4 years to excavate in the windows of opportunity afforded by falling water levels. And several tons of soil samples had to be brought back – precariously in a small boat [Fig. 25] – and wet-seived [Fig. 26] for charcoal.

- It is vital to make available the results of the work – whether survey or excavation.

- It is important to establish links with your local museum and the local and national bodies that have an interest in Scotland’s archaeology.

- Secure your funding.

The success of the Biggar Archaeology Group over the past 28 years is due to its adherence to these guidelines.