The bastle house was the first to be excavated, taking over a year to expose the building.

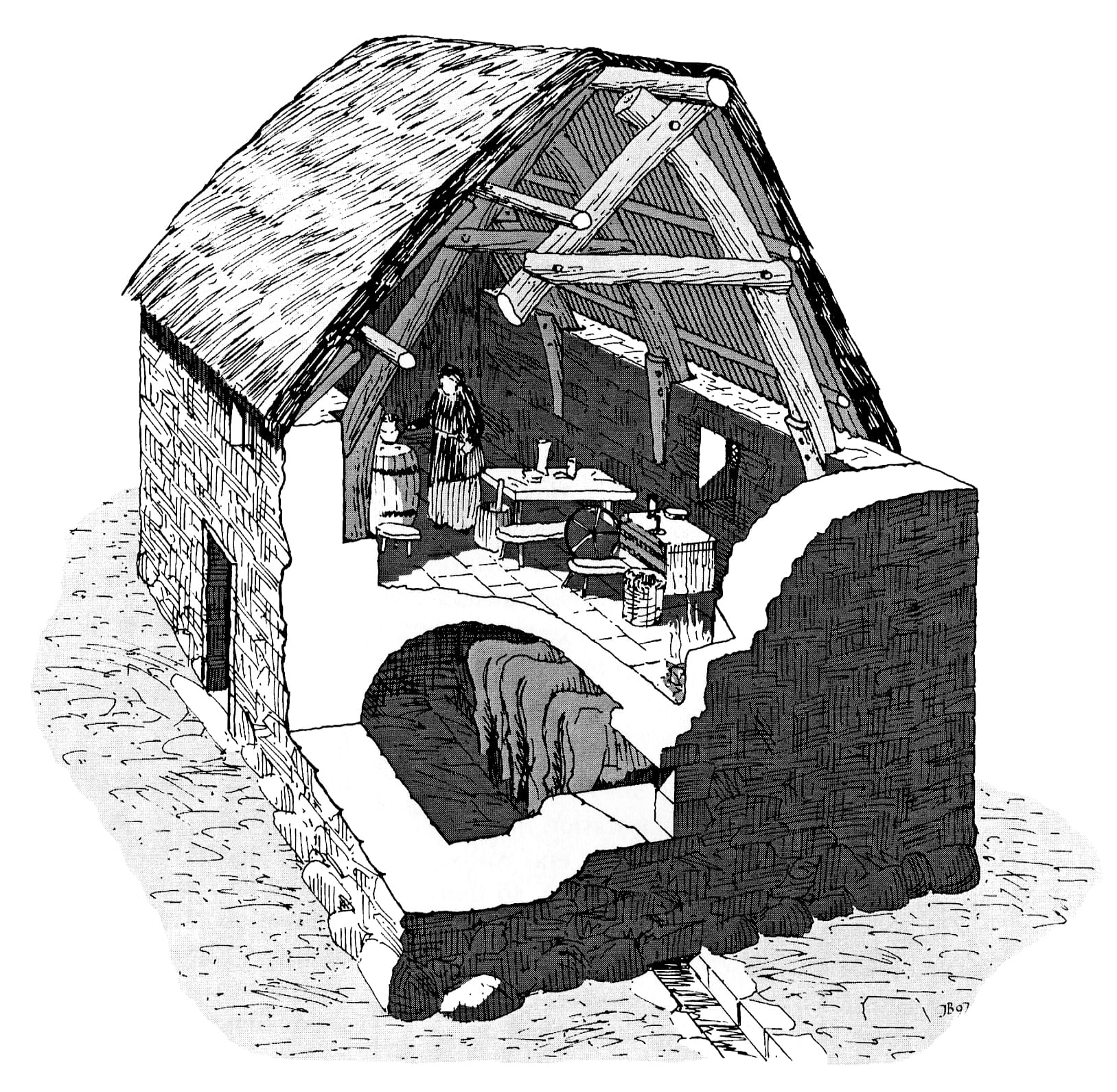

The house used high quality lime mortar for random rubble walls 3 ½ ft or just over 1m thick – a standard 16th century thickness for such buildings in Scotland. Strangely, the house was built askew. This may have been deliberate as parallels are found in other bastle houses (for example, Slacks bastle and Cramalt tower). The internal area of the byre is 8m x 4.5m. It is likely that the upper chamber forming the house would have been slightly wider, assuming that the upper long walls were thinner. The barrel vaulted basement, which would have been about 3m above the byre floor, was constructed first with the gables and then built into each end. The open drain on the floor discharges through a hole in the south wall and above this is the small slit window which gave limited light and ventilation to the ground floor byre.

The stairway is reasonably wide at 0.8m and led to the house above. It is an integral part of the building, unlike the English bastles where access to a secondary door for occupants in the upper floor was by a removable ladder. The mural stairs in Clydesdale bastles are one of several features, which distinguish them from their counterparts on the Borders. The door of the single entrance at Glenochar was protected from forces entry by at least one draw bar, which was cut into a door from of Dumfriesshire red sandstone. The contrast between the red doorway and the grey walls must have been striking.

There is no evidence for the appearance of the upper floor or the roof of the bastle. The habitable part of the bastle evidently had a stone floor and the stairway must have turned at right angles from a landing or platform to reach the house (known as a ‘scale and platt’ stair). We can deduce that there were only one or two tiny windows in the house walls, which would have been substantially thinner at that level. These windows may have been half glazed and were probably defended by iron bars set into sandstone sills and lintels (although none were found). The roof would have been of crick construction but, unlike Windgate House and Glendorch bastles, Glenochar did not have a slated roof – some form of thatch, perhaps straw and turf, covered crude timber work. It is not known if bastle houses had formal fireplaces built as part of the house design, but a fireplace (unfortunately now removed) at Nemphlar bastle near Lanark may have been original.

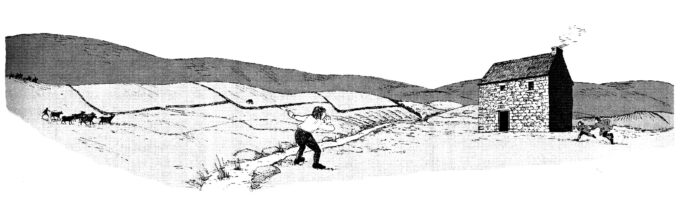

These farmhouses must have been an impressive contrast to most other dwellings in the neighbourhood. Only other bastle houses and the nearby castle at Crawford would have been built with mortar and stone in the early 17th century.

In 1986, the interior of Glenochar bastle was choked with demolition debris to a height of 3m and, within the lime and stone rubble, objects from the 17th century and sheep bone were found, the latter having been preserved by the lime. Items such as coins, buckles, clay tobacco pipes and pottery sherds must have been abandoned on the floor above when the final occupants left, but why the house was deserted is difficult to explain. Even if some calamity had taken place such as a burnt roof, the building would still have been superior to anything else around it and, one would have thought, worthy of repair. However, some time in the early 18th century, the vault finally collapsed or was pulled down. The masonry fell on to the byre floor, which was strewn with broken wine bottles and pottery all dating to that period. This resulted in earlier objects covering later ones – the opposite to what archaeologists normally find.

This clear relationship between objects from different periods helps to explain secondary features built into the basement. A supplementary doorway was created by the two wall ‘stumps’ and a timber door frame was installed. A fireplace (which was never used) was built or partially built against the north gable wall. These ‘add-ons’ may be explained thus: in the late 17th century, the upper floor is abandoned with objects lying about it. Perhaps at this time dressed sandstone from the entrance was removed for building elsewhere. Someone during the early 18h century decides to use the vaulted basement, which is still in tact, so they build a new entrance beneath the vault and create the fireplace. The new entrance would not allow easy access for cattle or a horse and the fireplace flue would have to go through the upper stair, which must therefore have been obsolete. The fireplace was certainly never used as such since there was no indication of heat on the stonework. It would appear that this late phase of occupation (as a house?) was of very short duration, before the final collapse of the upper floor, sealing in the 18th century bottle glass and pottery. This hypothetical sequence of events of not difficult to understand, but the reasons for abandoning such a fine building after perhaps only a hundred years or so of use are perplexing.

The bastle house restoration

Only the external faces of the south gable and the long east wall were visible prior to excavation. The rest of the building was buried under demolition material and covered in grass. The only visible feature was the small window in the gable , the interior being choked up to that level.

It has always been part of the project strategy to consolidate the remains of the bastle houses after excavation, since exposure to the elements causes further deterioration. Repairs were completed at the Windgate House by 1986, when over six tons of mortar was used just to cap the wall heads and to rebuild certain parts of the building, preserving the ruin for the foreseeable future.

At Glenochar, total consolidation of the ruin was necessary for several reasons. The building and site were designated a Schedules Ancient Monument after excavation placing any post-excavation works on the site under the control of Historic Scotland. Scheduled Ancient Monument Consent was granted to prepare the fermtoun as a visitor attraction and specifications for the work prepared in liaison with historic Scotland and , specifically for the bastle house, with the Scottish Lime Centre, specialist consultants for repairs to historic buildings using traditional materials. The bastle was deteriorating prior to excavation and this process would certainly have accelerated after the buried walls were exposed. It was essential to repair the building and , since the intention was to have the bastle as a visitor attraction, full consolidation was deemed most appropriate.

To that end, lime mortar and aggregates have been chosen to match as closely as possible the only additional masonry added to the building has been used to uphold the structure and seal off the wall-heads. Some parts of the wall faces are slightly recessed back from the original, to indicate they are modern. All the joints have been pointed to give the remains of the bastle their original appearance of some 400 years ago and to preserve the house.